BODY

MOVEMENT

I have always tried to render inner feelings through the mobility of

the muscles . . . --Auguste Rodin

You're the hardest guy to get anything out of. You don't even move your ears. --Vivian Regan to Philip Marlowe (The Big Sleep, 1939:60)

As an actor, Jimmy was

tremendously sensitive, what they used to call an instrument. You could see

through his feelings. His body was very graphic; it was almost writhing in pain

sometimes. He was very twisted, almost like a cripple or a spastic of some

kind. --Elia Kazan, commenting on

actor James Dean (Dalton 1984:53)

Concept. Any of several changes in the

physical location, place, or position of the material parts of the human form

(e.g., of the eyelids, hands, or shoulders).

Usage: The nonverbal

brain expresses itself through diverse motions of our body parts

(see, e.g., BODY LANGUAGE, GESTURE). That body movement is central to our

expressiveness is reflected in the ancient Indo-European root,

meue- ("mobile"), for the English word,

emotion.

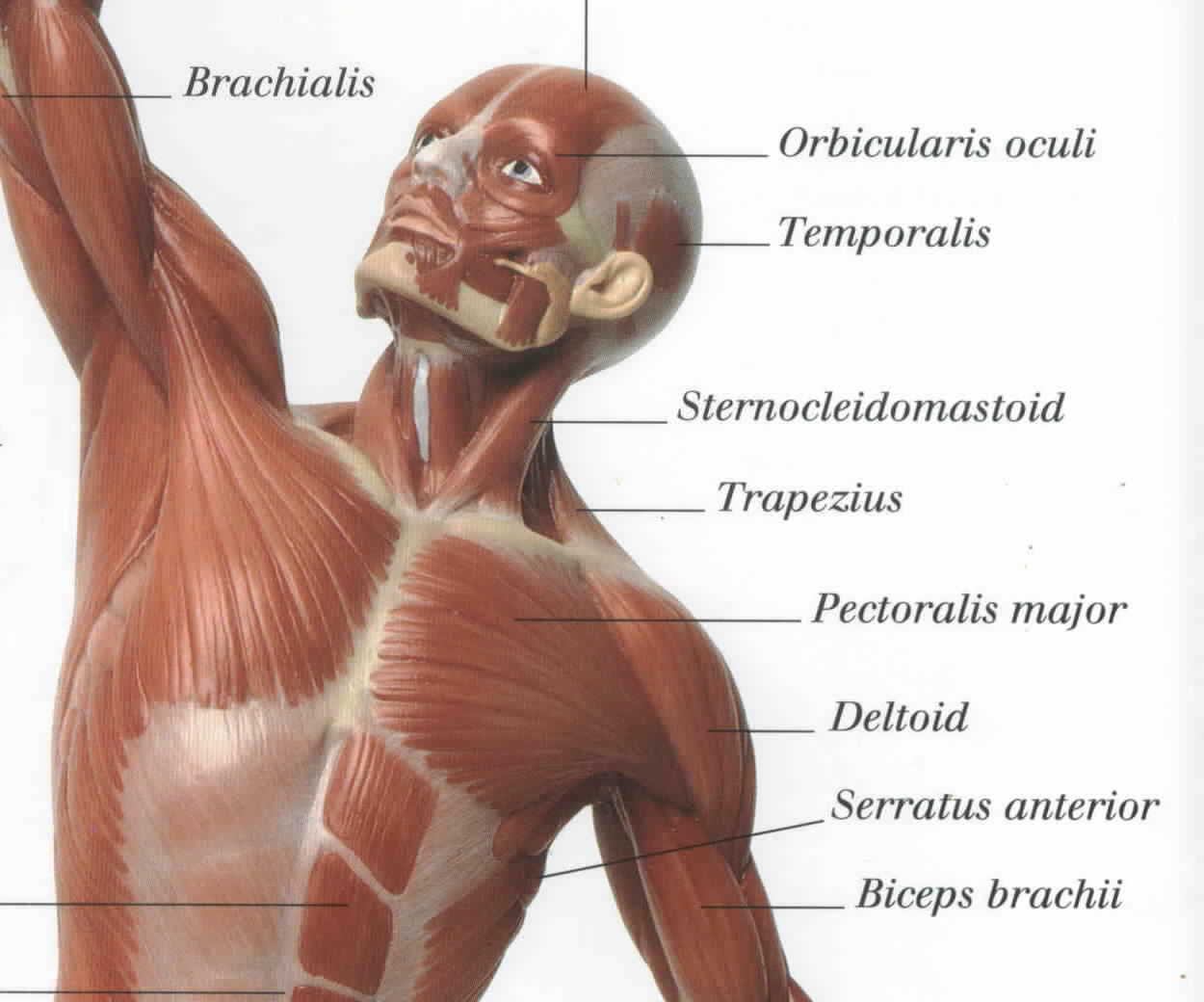

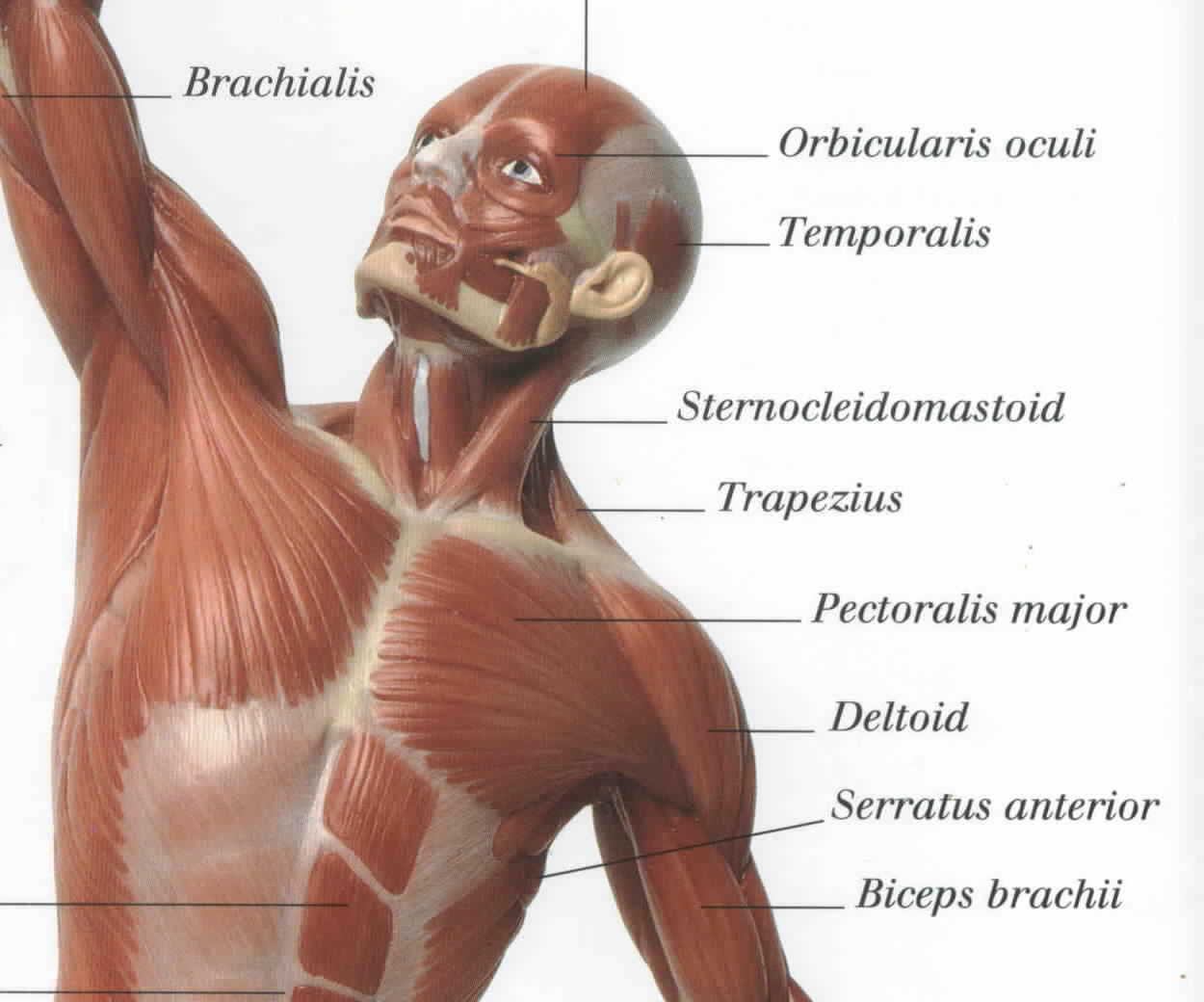

Anatomy. Our body consists of

a jointed skeleton moved by muscles. Muscles also move our internal

organs, the areas of skin around our face and neck, and our bodily

hairs. (When we are frightened, e.g., stiff, tiny muscles stand our hairs on

end.) The nonverbal brain gives voice to all its feelings, moods, and concepts

through the contraction of muscles: without muscles to move its parts, our

body would be nearly silent.

Anthropology. Stricken with a

progressive spinal-cord illness, the late anthropologist, Robert F. Murphy

described his personal journey into paralysis in his last book, The Body

Silent. As he lost muscle control, Murphy noticed "curious shifts and

nuances" in his social world (e.g., students ". . . often would touch my arm or

shoulder lightly when taking leave of me, something they never did in my walking

days, and I found this pleasant" [Murphy 1987:126]).

Confidence. "The physical confidence that he [Erik

Weihenmayer, 33, the first blind climber to scale Mount Everest] projects has to

do with having an athlete's awareness of how his body moves through space.

Plenty of sighted people walk through life with less poise and grace than Erik,

unsure of their steps, second-guessing every move" (Greenfeld

2001:57).

Media. In movies of the 1950s, such as Monkey

Business (1952) and Jailhouse Rock (1957), motions of the pelvic

girdles of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, respectively, had a powerful

influence on American popular culture.

Salesmanship. "Your

walk, entering and exiting, should be brisk and businesslike, yes. But once you

are in position, slow your arms and legs down" (Delmar

1984:48).

RESEARCH REPORT: "A nonverbal act

is defined as a movement within any single body area (head, face, shoulders,

hands, or feet) or across multiple body areas, which has visual integrity and is

visually distinct from another act" (Ekman and Friesen 1968:193-94).

E-Commentary: "I am searching for

the piece of influential advice that will help one of my employees to

communicate in a positive way nonverbally. Her boredom and impatience are so

evident. She shifts in her seat, rolls her eyes, and sighs during

meetings. It is disturbing to her co-workers and bad for morale. I have

explained to her it is not appropriate. She replies she can't hide the way she

feels. On the other hand, she wants to keep her job. So what can I do to get

through to her before she loses her job?" --T., USA (4/17/00

8:40:04 PM Pacific Daylight Time)

Neuro-notes I. Many nonverbal signals arise from ancient

patterns of muscle contraction laid down hundreds of millions of years ago in

paleocircuits of the spinal cord, brain stem, and

forebrain.

Neuro-notes II. Mirror neurons: "[Giacomo Rizzolatti's] discovery of mirror neurons is one of the major discoveries of the last 20 years in neuron science because it taught us several different lessons. One is . . . the appreciation that one has in one's brain, the capability of understanding another person's action, that when somebody does something, your own nervous systems goes us [sic] as if you're carrying out the action yourself although your hand doesn't move." (Source: Comments by Eric Kandel on PBS's "Charlie Rose Show" ("The Social Brain," January 10, 2010); http://www.charlierose.com/download/transcript/10820 [accessed December 19, 2012]; copyright 2010 Charlie Rose; transcription copyright 2010 CQ Transcriptions, LLC)

Neuro-notes III. Mirror neurons: ". . . associations naturally occur among the motor, somatosensory, vestibular, auditory, visual, and other inputs when a movement is executed. It is hypothesized that linking the observation of movement (visual input) to extant motor representations such that later observed actions can retrieve these stored patterns automatically can explain how the mirror neuron system develops" [Source: Pineda, Jaime A. (2008). "Sensorimotor Cortex as a Critical Component of an 'Extended' Mirror Neuron System: Does it Solve the Development, Correspondence, and Control Problems in Mirroring?" Behavioral and Brain Functions, 4:47 (Web document: http://www.behavioralandbrainfunctions.com/content/4/1/47 [accessed March 1, 2013])].

EAR MOVEMENT

Vestigial signs. To move the ears upward, forward or backward, through contractions of the outer ears' auriculares muscles. The movements may be go unnoticed, however, and may not play roles in interpersonal nonverbal communication.

Usage. Though an estimated ten-to-twenty percent of human beings are able to "wiggle" their ears, the movements may not transmit social or emotional information. Still, when picked up by electronic measuring devices, the ears' vestigial muscle contractions may reflect emotional arousal, such as, e.g., in happiness. Since linkage exists between the smile's zygomatic muscle and some of the outer ears' auriculares muscles, a strong smile may visibly move the ears. (N.B.: These muscles are innervated by the emotional facial nerve, cranial VII.)

Ear-flattening I. In addition to the above ear movements—which originated to orient the external ear flaps directionally to sound—ear-flattening originated to lower the ears in potentially dangerous or hostile conditions.

Ear-flattening II. Flattening occurs in many mammals, and in lower primates (prosimians), such as the bush baby (Galago sp.), it has become a social signal used to appease rivals. In higher primates (monkeys, apes and humans), flattening has ceased to exist as a sign due to an evolutionary reduction in ear musculature. But part of the signal has been retained. Scalp-retraction, originally part of the ear-flattening complex, occurs in macaques and baboons as a stereotyped, exaggerated display (Andrew 1965). Dominant members of some monkey genera (Macaca, Papio, Theropithecus, Mandrillus, Cynopithecus, Cebus and Cercocebus) raise the eyebrows in threat situations to expose light colored skin (van Hooff 1967)

Eyebrow-raise. In humans, the eyebrow-raise gesture has become a highly communicative, worldwide nonverbal sign.

See also EYEBROW-FLASH, EYEBROW-RAISE

JUMP

Body movement. To suddenly lift or spring off the ground through combined muscular contractions of the arms, legs and feet.

Nonverbal usage. In addition to jumping's role in locomotion (e.g., in hurdles and steeplechase), it may be used to express strong emotions such as anger and joy. When told to turn off his smart phone, e.g., a child may jump up and down in anger and beat the air with fisted hands. When told she just won a new car, a woman may jump up and down and happily clap her hands for joy.

Media. Perhaps the best known temper-tantrum jump is that of the Disney cartoon character, Donald Duck.

Freudensprung. Excited jumping has been studied in chimpanzees, dogs and rats. Known as freudensprung ("joy jumps"), the behaviors may be glossed as intention cues of quadrupedal locomotion.

Neuro-notes. Sudden anger may release noradrenaline into the bloodstream to stimulate angry jumping outbursts. Sudden joy, as when one's soccer team scores a goal, may release dopamine to boost bodily energy and release excited jumps. U.S. baseball teams may triumphantly jump up and down in joyful unison after winning a playoff game (see ISOPRAXISM).

See also TRIUMPH DISPLAY.

RHYTHMIC REPETITION

Reflex-like cue. Rhythmic repetition is a key ingredient in many nonverbal signs, signals and cues. It includes repeated, stereotyped body movements that may become automatic over time. The rhythmic-repetition maxim may be encoded in architecture, art, biology, clothing, dance, music and diverse additional nonverbal--and verbal--domains.

Usage. In the architectural domain, a gazebo exemplifies how rhythmic repetition may be used (see GAZEBO). Nonverbally, the harmonic repetition of its design features--of its columns, cupolas, and horizontal-trim--serve to unify the gazebo's structure, add narrative flow and simulate a sense of motion.

Neuro-notes. In biology, rhythmic repetition dates to ca. 500 mya in vertebrate spinal-cord, brain-stem and cortical-motor areas (Ghez 1991b). "Once initiated, the sequence of relatively stereotyped movements may continue almost automatically in reflex-like fashion" (Ghez 1991b, p. 534). Neurologically, rhythmic repetition may stimulate a sense of movement.

[We are exploring the relationship of rhythmic-communicative body movements and Circadian Rhythms (CRs). Cellular and neural circuits for CRs may underlie all human communication, verbal and nonverbal (afferent and efferent). Below, we share a provocative abstract from:

[Poeppel, David, and M. Florencia Assaneo (2020). "Speech Rhythms and Their Neural Foundations," Cell (Vol. 21, pp. 322-334).

[Abstract

["The recognition of spoken language has typically been studied by focusing on either words or their constituent elements (for example, low-level features or phonemes). More recently, the 'temporal mesoscale' of speech has been explored, specifically regularities in the envelope of the acoustic signal that correlate with syllabic information and that play a central role in production and perception processes. The temporal structure of speech at this scale is remarkably stable across languages, with a preferred range of rhythmicity of 2 - 8 Hz. Importantly, this rhythmicity is required by the processes underlying the construction of intelligible speech. A lot of current work focuses on audio-motor interactions in speech, highlighting behavioural and neural evidence that demonstrates how properties of perceptual and motor systems, and their relation, can underlie the mesoscale speech rhythms. The data invite the hypothesis that the speech motor cortex is best modelled as a neural oscillator, a conjecture that aligns well with current proposals highlighting the fundamental role of neural oscillations in perception and cognition. The findings also show motor theories (of speech) in a different light, placing new mechanistic constraints on accounts of the action–perception interface."

"A novel reticular node in the brainstem synchronizes neonatal mouse

crying with breathing," by Xin Paul Wei, Matthew Collie, Bowen Dempsey, Gilles Fortin, and Kevin Yackle

Correspondence: kevin.yackle@ucsf.edu; https://doi.org/10.1016/. In j.neuron, 2021.12.014

The Summary below is from the above source.

"Human speech can be divided into short, rhythmically timed elements, similar to syllables within words. Even our cries and laughs, as well as the vocalizations of other species, are periodic. However, the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the tempo of mammalian vocalizations remain unknown. Furthermore, even the core cells that produce vocalizations remain ill-defined. Here, we describe rhythmically timed neonatal mouse vocalizations that occur within single breaths and identify a brainstem node that is necessary for and sufficient to structure these cries, which we name the intermediate reticular oscillator (iRO). We show that the iRO acts autonomously and sends direct inputs to key muscles and the respiratory rhythm generator in order to coordinate neonatal vocalizations with breathing, as well as paces and patterns these cries. These results reveal that a novel mammalian brainstem oscillator embedded within the conserved breathing circuitry plays a central role in the production of neonatal vocalizations" (Wei et al. 2021).

Waves

"The very fact that the majority of human communication takes place via waves may not be a casual fact – after all, waves constitute the purest system of communication since they transfer information from one entity to the other without changing the structure or the composition of the two entities. They travel through us and leave us intact, but they allow us to interpret the message borne by their momentary vibrations, provided that we have the key to decode it. It is not at all accidental that the term information is derived from the Latin root forma (shape) – to inform is to share a shape." (Source: [https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200929-what-your-thoughts-sound-like])

Rhythmic speech

"Moving in time to a steady beat is closely linked to better language skills, a study suggests.

"People who performed better on rhythmic tests also showed enhanced neural responses to speech sounds.

"The researchers suggest that practising music could improve other skills, particularly reading.

"In the Journal of Neuroscience, the authors argue that rhythm is an integral part of language.

"We know that moving to a steady beat is a fundamental skill not only for music performance but one that has been linked to language skills," said Nina Kraus, of the Auditory Neuroscience Laboratory at Northwestern University in Illinois."

More to come . . .

See also DANCE, PALEOCIRCUIT.

See also FACIAL

EXPRESSION, INTENTION CUE,

POSTURE.

YouTube Video: "I have always tried to render inner feelings through the mobility of the muscles." Watch a one minute video showing Auguste Rodin's sculpted body movements, frozen in time.

Copyright

1998 - 2022 (David B.

Givens/Center for Nonverbal Studies)

Detail of illustration from The Visual Dictionary of the Human Body (p. 22; copyright 1991 by

Dorling Kindersley, Inc., 95 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10016)