FACIAL

EXPRESSION

I will often fly great

distances to meet someone face to face . . . . --Mark

H. McCormack (What They Don't Teach You at Harvard

Business School, 1984:9)

Sign.

The act of communicating a mood, attitude, opinion, feeling, or other message by contracting the muscles of the face.

Usage: The combined expressive force of our mobile chin, lip, cheek,

eye, and brow muscles is without peer in the animal kingdom. Better than any

body parts, our faces reveal emotions, opinions, and moods. While we learn to

manipulate some expressions (see, e.g., SMILE), many unconscious facial expressions (see, e.g.,

LIP-POUT, TENSE-MOUTH, and TONGUE-SHOW) reflect our true feelings and hidden

attitudes. Many facial expressions are universal, though most may be shaped by

cultural usages and rules (see below, Culture).

Summary of facial expressions. 1. Nose:

nostril flare (arousal). 2. Lips:

grin (happiness, affiliation, contentment); grimace (fear);

lip-compression (anger, emotion, frustration); canine snarl

(disgust); lip-pout (sadness, submission, uncertainty);

lip-purse (disagree); sneer (contempt; see below, Sneer).

3. Brows: frown (anger, sadness,

concentration); brow-raise (intensity). 4.

Tongue: tongue-show (dislike, disagree). 5.

Eyelids: flashbulb eyes (surprise); widened

(excitement, surprise); narrowed (threat, disagreement); fast-blink (arousal); normal-blink

(relaxed). 6. Eyes: big pupils (arousal, fight-or-flight); small pupils (rest-and-digest); direct-gaze (affiliate,

threaten); gaze cut-off (dislike, disagree); gaze-down (submission, deception); CLEMS

(thought processing). (NOTE: See

individual entries elsewhere in The

Nonverbal Dictionary.)

Child development. ". . .

all children, regardless of cultural background, show the same maturation

process when it comes to the basic emotional expressions [e.g., of anger, fear,

and joy]" (Burgoon et al. 1989:350; see below, RESEARCH

REPORTS).

Culture. "Japanese are taught to mask negative

facial expressions with smiles and laughter and to display less facial affect

overall, leading some Westerners to consider the Japanese inscrutable (Friesen,

1972; Morsbach, 1973; Ramsey, 1983)" (Burgoon et al. 1989:193).

Embryology. The nerves and muscles that open and close our mouth

derive from the 1st pharyngeal arch, while those that constrict our

throat derive from the 3rd and 4th arches. In the disgusted or

"yuck-face," cranial VII contracts orbital muscles to narrow

our eyes, as well as corrugator and associated muscle groups to lower

our brows. (Each of these muscles and nerves derives from the 2nd

pharyngeal arch.) We may express positive, friendly, and confident moods by

dilating our eye, nose, throat, and mouth openings--or we may show

negative and anxious feelings (as well as inferiority) by constricting

them. Thus, the underlying principle of movement established in the jawless

fishes long ago remains much the same today: Unpleasant emotions and stimuli

lead cranial nerves to constrict our eye, nose, mouth, and throat openings,

while more pleasant sensations widen our facial orifices to incoming

cues.

Evolution I. In the Jurassic period, mammalian

faces gradually became more mobile (and far more expressive) than the rigid

faces of reptiles. Muscles which earlier controlled the pharyngeal

arches (i.e., the primitive "gill" openings) came to move mammalian

lips, muzzles, scalps, and external ear flaps. Nerve links from the emotional

limbic system to the facial muscles--routed through the

brain stem's facial and trigeminal nerves (cranial VII and

V)--enable us to express joy, fear, sadness,

surprise, interest, anger, and disgust

today.

Evolution II. That a nose-stinging whiff of ammonium carbonate can

cause our face to close up in disgust shows how facial expression,

smell, and taste are linked. The connection traces back to the ancient muscles

and nerves of the pharyngeal arches of our remote Silurian ancestors. Pharyngeal

arches were part of the feeding and breathing apparatus of the jawless fishes;

sea water was pumped in and out of the early pharynx through a series of gill

slits at the animal's head end. Each arch contained a visceral nerve

and a somatic muscle to close the gill opening in case dangerous

chemicals were sensed. Very early in Nonverbal

World, pharyngeal arches were programmed to constrict in

response to noxious tastes and smells.

Gag reflex. The ancient

pattern is reflected in our faces today. In infants, e.g., a bitter taste shows

in lowered brows, narrowed eyes, and a protruded

tongue--the yuck-face expression pictured on poison-warning labels. A bad

flavor causes baby to seal off her throat and oral cavity as cranial nerves

IX and X activate the pharyngeal gag reflex. Cranial

V depresses the lower jaw to expel the unpleasant mouthful (then closes

it to keep food out), as cranial XII protrudes the

tongue.

Gender differences. "Not surprisingly, women have a

general superiority over men when it comes to decoding facial expressions . . ."

(Burgoon et al. 1989:360).

Mimicking. Research indicates that

mimicking another's face elicits empathy (Berstein et al., 2000).

Primatology. 1. In our closest primate relatives, the Old World

monkeys and apes, the following facial expressions have been identified: alert

face, bared-teeth gecker face, frowning bared-teeth scream face, lip-smacking

face, pout face, protruded-lips face, relaxed face, relaxed open-mouth face,

silent bared-teeth face, staring bared-teeth scream face, staring open-mouth

face, teeth-chattering face, and tense-mouth face (Van Hooff 1967). 2.

"Andrew (1963, 1965) held that facial expressions were originally natural

physical response to stimuli. As these responses became endowed with the

function of communication, they survived the various stages of evolution and

were passed along to man" (Izard 1971:38; cf. NONVERBAL

INDEPENDENCE).

Sneer. In the sneer, buccinator

muscles (innervated by lower buccal branches of the facial nerve) contract to

draw the lip corners sideward to produce a sneering "dimple" in the cheeks (the

sneer may also be accompanied by a scornful, upward eye-roll). From videotape

studies of nearly 700 married couples in sessions discussing their emotional

relationships with each other, University of Washington psychologist, John

Gottman has found the sneer expression (even fleeting episodes of the cue) to be

a "potent signal" for predicting the likelihood of future marital disintegration

(Bates and Cleese 2001). In this regard, the sneer may be decoded as an

unconscious sign of contempt.

RESEARCH

REPORTS: So closely is emotion tied to facial expression that it

is hard to imagine one without the other. 1. The first major

scientific study of facial communication was published by Charles Darwin in

1872. Darwin concluded that many expressions and their meanings (e.g., for

astonishment, shame, fear, horror,

pride, hatred, wrath, love, joy,

guilt, anxiety, shyness, and modesty) are

universal: "I have endeavoured to show in considerable detail that all the chief

expressions exhibited by man are the same throughout the world" (Darwin

1872:355). 2. Sylvan S. Tomkins found eight "basic" facial

emotions: surprise, interest, joy, rage,

fear, disgust, shame and anguish (Tomkins

1962; Carroll Izard proposed a similar set of eight [Izard 1977]).

3. Studies indicate that the facial expressions of happiness, sadness, anger, fear,

surprise, disgust, and interest are universal across cultures

(Ekman and Friesen 1971). 4. ". . . the emotion process includes a motor

component subserved by innate neural programs which give rise to universal

facial patterns. These patterns are subject to repression, suppression, and

other consequences of socialization during childhood and adolescence" (Izard

1971:78).

E-Commentary I: The face entranced. "I have observed that when

a woman absent-mindedly knots a lock of her hair on a finger or twists her ring

on her finger, she often displays a trance

like facial expression--i.e., her glance seems to look

far away, her face has no expression, the right and left sides of her face are

more symmetrical, she slows or loses her eye-blink, her pupils dilate, she

half-opens her mouth as her chin falls down (her jaw appears relaxed),

and her body appears fairly passive or motionless. I have seen the same

nonverbal pattern in men, as well." --Dr. Marco Pacori, Institute of Analogic

Psychology, Milano, Italy (3/29/00 9:17:37 AM Pacific Standard Time)

E-Commentary II: "I am looking

for help in analyzing the natural expression on my face. I'm a 52 year old male

and I believe others sense my facial expression as one of being angry when I'm

not the least bit angry. I believe that it severely limits healthy relationships

as well as my income. (I talk to people all day in sales.) Although my mate and

I are very happy, I'm looking for a change, but don't know where to start. --R.

C. (9/10/01 8:01:23 PM Pacific Daylight Time)

Neuro-notes I. 1. The facial nerve nucleus of the brain stem

contains motor neurons that innervate the facial muscles of expression (Willis

1998F). 2. "The facial muscles and the facial nerve and its various

branches constitute the most highly differentiated and versatile set of

neuromuscular mechanisms in man" (Izard 1971:52).

Neuro-notes

II. "The homologue of Broca's area in nonhuman primates is the part of the

lower precentral cortex that is the primary motor area for facial musculature. .

. . electrical stimulation of this area in squirrel monkeys . . . yields

isolated movements of the monkey's lips and tongue and some laryngeal activity

but no complete vocalizations" (Lieberman 1991:106; see SPEECH).

Neuro-notes III. 1. "The facial nucleus [of the albino rat]

contains numerous medium-caliber, intensely immunoreactive dynorphin fibers,

especially in the intermediate subdivision of the nucleus . . ." (Fallon and

Ciofi 1990:31). 2. "The functions of these projections are unknown, but

it is likely that dynorphin and enkephalin would modulate motor neurons

enervating the facial musculature, especially those in the intermediate division

controlling the zygomatic, platysma and mentalis muscles" (Fallon and Ciofi

1990:31-2).

Neuro-notes IV. Mirror neurons: Mirror-neuron properties for perceiving and creating facial expressions are found in the inferior parietal lobe (IPL: involved in tool usage and perception of emotions in facial expressions), frontal operculum (fO: involved in cognitive and perceptual motor processing), and premotor cortex (involved in spatial and sensory guidance of movement, and in understanding the movements of others) (Haxby and Gobbini 2011:101). "Facial expressions contain both motor and emotional components. The inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) and posterior parietal cortex have been considered to compose a mirror neuron system (MNS) for the motor components of facial expressions, while the amygdala and insula may represent an 'additional' MNS for emotional states" [van der Gaag, C., Minderaa, R. B., and C. Keysers, "Facial Expressions: What the Mirror Neuron System Can and Cannot Tell Us," Social Neuroscience, 2007; 2(3-4):179-222].

Neuro-notes V. Mirror neurons: The amygdala responds most strongly to viewed facial expressions of fear, while the anterior insula responds to viewed facial expressions of disgust (Haxby and Gobbini 2011:102). "The activity in these areas suggests that understanding the emotional meaning of expressions involves evoking the emotion itself--a simulation or mirroring of another's emotion that is analogous to the putative role of the hMNS [human mirror neuron system] in simulating or mirroring the motor actions of another" (Haxby and Gobbini 2011:102).

Neuro-notes VI. Mirror neurons: Learning influences young children's mirror neurons for reading facial expressions. Consider Pier Francesco Ferrari's abstract for the 2012 conference on "Mirror Neurons: New Frontiers 20 Years After Their Discovery": "In the course of early development mirror neurons for face gestures are strongly influenced by social interactions and can be shaped by the affective feedback of the caregiver."

Neuro-notes VII. Mirror neurons: Monkeys can imitate facial expressions at birth. Mirror neurons in monkeys respond to facial expressions of emotion (e.g., to lip-smacking). (Source: Pier Francesco Ferrari's abstract for the 2012 conference on "Mirror Neurons: New Frontiers 20 Years After Their Discovery")

Neuro-notes VIII. Mirror neurons: "Accordingly, empathy is a routine involuntary process, as demonstrated by electromyographic studies of invisible muscle contractions in people's faces in response to pictures of human facial expressions. These reactions are fully automated, occurring even when we are unaware of what we saw (Dimberg et al. 2000 [Dimberg, U., Thunberg, M., and K. Elmehed (2000). "Unconscious Facial Reactions to Emotional Facial Expressions," in Psychological Science, Vol. 11, pp. 86-89])" [p. 59; source: de Waal, Frans B. M. (2007). Chapter 3: "The 'Russian Doll' Model of Empathy and Imitation," in Braten, Stein (Ed.), On Being Moved: From Mirror Neurons to Empathy (2007; Amsterdam: John Benjamins), pp. 49-70].

See also BLANK FACE.

FACIAL ACTION TEST (DIRECTED)

Design. Designed by Ekman, Levenson, and Friesen (1983) this task (s) explores physiological responses to facial expressions. In the Directed Facial Action task, individuals are asked to move their facial muscles in certain ways, but are not told the actual emotion they are expressing. Through the movement of the various facial muscles, participants form the prototypical emotional facial expression.

Research. Research by Levenson and Ekman (2002) has been consistent in discovering that facial expressions which involve anger, fear, and sadness produce greater increases in heart rate than those expressions which show disgust.

Other research has found that the portrayal of fear compared with portraying calmness causes an increase in skin conductance and pulse rate (McCaul et al., 1982). The task has been validated across various cultures and age groups (e.g., Levenson et al. 1992, 1991).

(John White)

Copyright 1998 - 2020 (David B. Givens & John White) /Center for Nonverbal Studies)

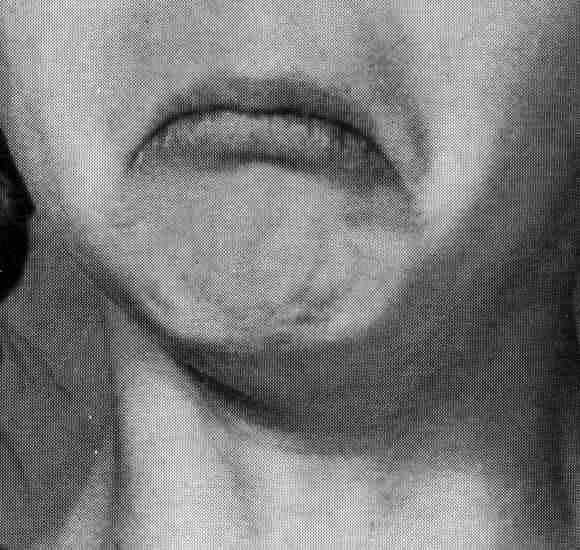

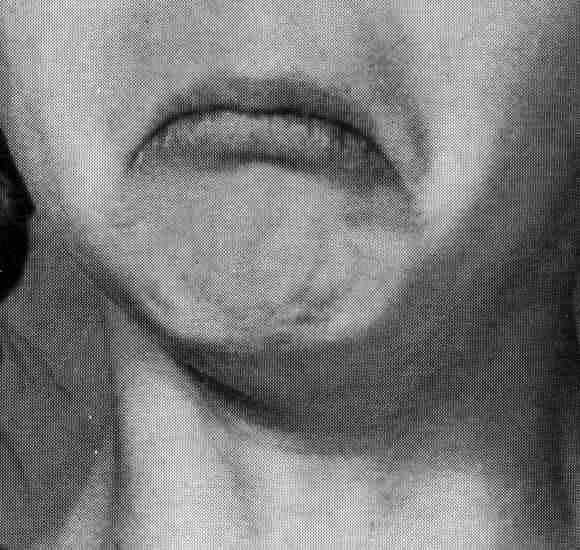

Detail of photo showing contraction of depressor anguli oris (pulling down lip corners [in sadness]) and mentalis muscles (dimpling chin [in lip-pout]; mentalis protrudes and everts the lower lip; the dimpled-chin expression correlates well with doubt, disdain, and negative emotions [picture copyright 1949 by The Williams and Wilkins Co.])