Neuro term. 1.A paleocircuit is a preconfigured module, pathway, or network of nerve cells in the forebrain, brain stem, or spinal cord (such as, in the latter, e.g., reflex arcs and rhythmic Central Processing Generators [CPGs]) preserved in living nervous tissue utilized in nonverbal communication. 2. A pre-established neural program, of great age, for sending (or receiving) nonverbal signs. 3. An ancient, neural "platform" for bodily expression, configured millions of years before the advent of cortical circuits for speech.

Usage: Paleocircuits (such as rhythmic Central Pattern Generators [CPGs]) are modules and passageways preserved in living nervous tissue, much as fossils have solidified no longer living tissues into lifeless stone. Tracing the paleocircuits of nonverbal signs helps us unravel their origin, evolution, and meaning.

Anatomy. Paleocircuits channel the electrochemical impulses required for muscles to contract, e.g., as visible signs of happiness or sadness, in the nonverbal present. As "living fossils," paleocircuits preserve information about gestures from the nonverbal past as well.

Evolution. In the aquatic brain and spinal cord, e.g., ancient networks of motor neurons and interneurons evolved to control the body movements of our oldest animal ancestors, the jawless fishes. From these ancient neuronal micropaths, instructions reached local muscle groups to move individual body parts. From the very beginning of vertebrate life, microscopic systems of spinal interneurons stood between motor neurons and sense receptors, affecting the input and outflow of nonverbal signs. Thus, it was established early on that the spinal cord should be more than a passive pipeline to carry sensory messages to the brain and motor signals back to the body. Like the brain itself, our spinal cord is replete with paleocircuits which have "minds of their own" (e.g., for managing tactile withdrawal, and the oscillating, rhythmic movements of walking).

Neuro-notes. 1. Paleocircuits are subcortical nerve nets and pathways which link bodily arousal centers (of the reticular activating system), emotion centers (of the hypothalamus, amygdala, and cingulate gyrus), and motor areas of the forebrain (basal ganglia) and midbrain (superior and inferior colliculi), with muscles for the body movements required by nonverbal signs. 2. "Only a few of the descending [motor] pathways [from the brain] synapse directly on spinal cord motor neurons. Instead, most of the descending projections influence the activity of interneurons that are interposed in reflex circuits and thus alter ongoing spinal reflex activity" (Willis 1998E:186).

Copyright 1998 - 2022 (David B. Givens/Center for Nonverbal Studies)

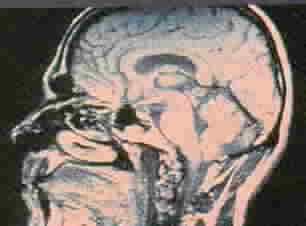

Photo of imaged brain (from Kandel et al. 1991; copyright 1991 by Appleton & Lange)

CENTRAL PATTERN GENERATOR

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780080450469019446

"Central pattern generators are neural circuits that can produce rhythmic network activity in the absence of timing cues from sensory feedback or descending pathways. This activity underlies behaviors such as locomotion and breathing. A variety of invertebrate and vertebrate preparations have provided insights into how rhythmic motor patterns are generated at the cellular and circuit level; how they are controlled by higher centers, sensory feedback, and neuromodulatory input; and how networks are coordinated to yield different behaviors. This work has elucidated a number of general principles governing network function and dynamics."

Spinal CPGs & Reflex Arcs

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2012.00183/full

"This article provides a perspective on major innovations over the past century in research on the spinal cord and, specifically, on specialized spinal circuits involved in the control of rhythmic locomotor pattern generation and modulation. Pioneers such as Charles Sherrington and Thomas Graham Brown have conducted experiments in the early twentieth century that changed our views of the neural control of locomotion. Their seminal work supported subsequently by several decades of evidence has led to the conclusion that walking, flying, and swimming are largely controlled by a network of spinal neurons generally referred to as the central pattern generator (CPG) for locomotion. It has been subsequently demonstrated across all vertebrate species examined, from lampreys to humans, that this CPG is capable, under some conditions, to self-produce, even in absence of descending or peripheral inputs, basic rhythmic, and coordinated locomotor movements. Recent evidence suggests, in turn, that plasticity changes of some CPG elements may contribute to the development of specific pathophysiological conditions associated with impaired locomotion or spontaneous locomotor-like movements. This article constitutes a comprehensive review summarizing key findings on the CPG as well as on its potential role in Restless Leg Syndrome, Periodic Leg Movement, and Alternating Leg Muscle Activation. Special attention will be paid to the role of the CPG in a recently identified, and uniquely different neurological disorder, called the Uner Tan Syndrome."