Straight dark brows with strong bone under them. A forehead wide rather than high, a mat of dark clustering hair, a thin short nose, a wide mouth. A chin that had strong lines but was small for the mouth. A face that looked a little taut, the face of a man who would move fast and play for keeps. --Private detective Philip Marlowe's description of Terence Regan's photograph (The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler, 1939, p. 123-24)

Identification. Those definitive features of a face

with which to establish its age, sex, attractiveness, and identity.

Usage: Despite an advanced ability to recognize and recall thousands of faces (see FACIAL RECOGNITION), we are unable to describe individual faces adequately in words. Witnesses at crime scenes, e.g., can offer police few verbal clues of facial I.D.

Identity clues. Our brain's innate ability to recognize faces far exceeds that of any spoken language to describe them. Identity clues used by the Chicago Police, e.g., consist of general, all-purpose words such as a. high, low, wide, and narrow foreheads; b. smooth, creased, and wrinkled skin; c. long, wide, flat, pug, and Roman noses; d. wide, narrow, and flared nostrils; e. sunken, filled-out, dried, oily, and wrinkled cheeks; f. prominent, high, low, wide, and fleshy cheek bones; g. corners-turned-up, down, and level for the mouth; h. thin, medium, and full upper and lower lips; i. double chin, protruding Adam's apple, and hanging jowls for necks; and j. round, oval, pointed, square, small, and double chins.

Prehistory. That linguistic labels for the face pale in comparison to those for consumer products (see, e.g., FOOTWEAR) is because our primate face "speaks for itself" and has done so for millions of years. The need to describe faces in words is a recent development dating back only a few thousand years to adaptations for city life, i.e., for urban crime and increasing numbers of strangers. (N.B.: Recognizing and remembering faces involves emotion centers of the brain, which are addressed only indirectly by speech centers.)

RESEARCH REPORTS: 1. Researchers have isolated facial traits preferred, perhaps, by all human beings. Facial "cuteness," e.g.--a set of immature features and youthful proportions--is found to be generally attractive in the male and female face. Cuteness (i.e., the infantile schema) was originally identified in mammals (including human beings) by Konrad Lorenz (1939). 2. Japanese and Caucasian men and women prefer high cheekbones and such infantile traits as a. thin jaws, b. large eyes, c. a short distance between the mouth and chin, and d. a short distance between the nose and mouth (Perrett, May and Yoshikawa 1994). 3. Another preferred trait is symmetry between a face's right- and left-hand sides. In a review of symmetry in mate selection, Paul Watson and Randy Thornhill concluded, e.g., that animals from scorpion flies to zebra finches show a preference for symmetrical patterns and shapes (perhaps because asymmetry is a sign of weakness or disease; Watson and Thornhill 1994). Thornhill applied the findings to human beings by studying college student ratings of young adult faces (through photos showing a range of vertical and horizontal symmetry or its lack): subjects rated symmetrical faces most attractive.

Evolution. Our face has become more baby-like (and less intimidating) through time. The wide jaws and broad dental arch of our ancestor, Homo habilis (ca. 2.3 m.y.a.), e.g., belonged to a fearsome-looking face with great biting power. Our own lower face's comparatively smaller features are crouched beneath an immense, bulbous--i.e., infantile--forehead.

See also FACIAL BEAUTY, FACIAL EXPRESSION, LOVE SIGNAL.

Copyright 1998 - 2016 (David B. Givens/Center for Nonverbal Studies)

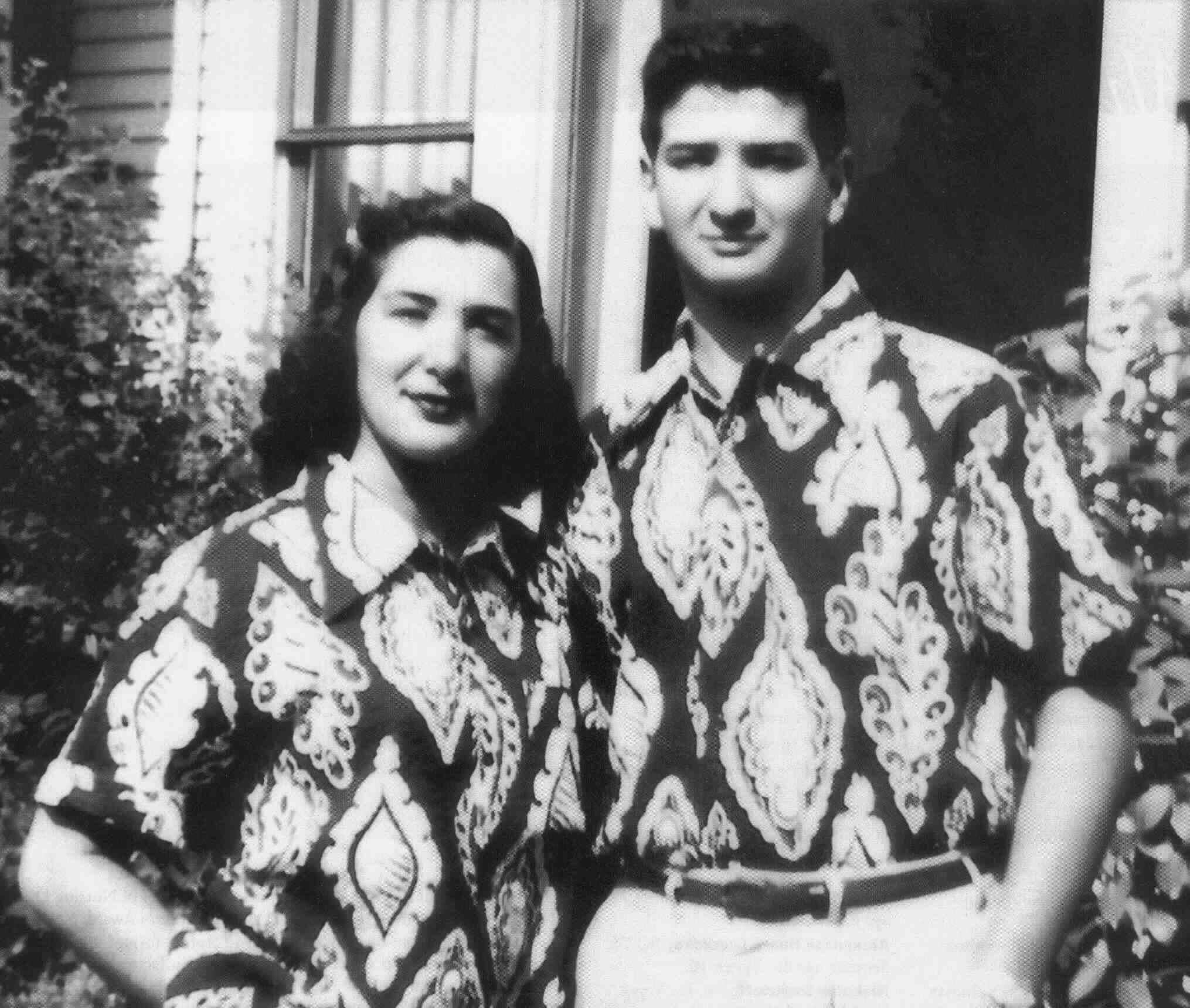

Vintage photo of a sister and brother (New Jersey, USA; picture credit: unknown)