OBJECT

FANCY

Among three to five-year-old children in nursery schools,

fights occur over property and little else. --N.G.

Blurton Jones (1967:355)

In more severe forms [of the grasping

reflex], any visual target will elicit manual reaching followed by tight

grasping. --M. Marsel Mesulam (1992:696)

Emotion. 1. The desire to pick up,

handle, and hold a material object, especially a consumer

product of elegant design. 2. The urge to touch,

own, arrange, collect, display, or talk about a manufactured human artifact.

3. The motivation for compulsive shopping.

Usage: Products "speak" to us nonverbally as tangible, material

gestures. Their design features (e.g., the shine,

shape, and smoothness of a platinum bracelet) send compelling

messages to capture our attention. That we respond to their appeal shows in the

sheer number of artifacts we possess. Our personality may be caricatured by the

object(s) we desire, e.g., jewelry, boats, shoes, and so on. We may hold treasured artifacts with

two hands, in a gentle, caressing embrace between the tactile pads of our thumbs

and forefingers. Forever beckoning from TV monitors, mail-order catalogues, and

shelves, products gesture until we answer their call.

Psychology. Our

aversion to the seizure by another of an object we are using may be innate

(Thorndike 1940).

RESEARCH REPORTS: 1. Communication

about material objects begins in infancy, after the age of six months

(Trevarthen 1977:254). 2. The average U.S. household stockpiles

a greater supply of consumer goods than its members want, need, or use.

3. By the age of five, the average American child has owned 250

toys.

Neuro-notes. The "magnetic effect triggered by objects" originates

with the innate grasping reflex. Subsequently, it involves a balance

a. between the parietal lobe's control of object

fancy, and b. the frontal lobe's "thoughtful

detachment" from the material world of goods (Mesulam 1992:697). In patients

with frontal lobe lesions, the mere sight of an artifact is "likely to elicit

the automatic compulsion to use it," while lesions in the parietal network

"promote an avoidance of the extrapersonal world" (Mesulam 1992:697).

See

also BARBIE DOLL.

GIFT

Presented item. 1. A present proffered by one person or group to another. Items may include life forms (e.g., puppies, roses), property (e.g., automobiles, land) and "things" (e.g., socks, necklaces, marbles and rings). 2. Nonverbally, gifts may become highly valued possessions through their emotional connection to givers (see EMOTION). 3. As signs, gifts are more than simply material things, but are material means to social ends.

Usage. Usually accompanied by words (e.g., written in cards or on tags, or spoken face-to-face), nonverbal gifts may be used to express appreciation, to mark anniversaries or to show love. Used to strengthen social bonds, they are powerful emotional signs that may call for reciprocation and exchange.

Nonverbal exchange. Anthropologists study gift giving as a nonverbal means of exchange. Gifts themselves lack the faculty of speech but communicate essential messages and meanings apart from words. Since the 1925 publication of French sociologist Marcell Mauss's classic work, The Gift, ethnologists have recognized the immense power of giving in human relationships. Mauss (1872-1950) taught that gifts are never free. Anthropologists today agree that when accepted, gifts incur strong obligations. Accepting a gift carries an implicit obligation to reciprocate in kind (Givens 2008).

Influence. Though generally positive, gifts may have a negative face in "influence peddling." In U.S. politics, e.g., one of the most notorious Washington, DC lobbyists, Jack A. Abramoff (1959- ), used gift-giving (vacation trips, tickets to football games, free meals at his restaurant and cash) to wield power on Capitol Hill (Givens 2008). After pleading guilty to charges relating to bribery, Abramoff spent four years in prison.

Apology roses. Gifts may be tendered as nonverbal signs to suggest, "I am sorry." As Vicki Crompton wrote in Saving Beauty from the Beast, "And of course there are the roses. They appear and reappear in many of the girls' stories" (Crompton and Kessner 2003, p. 20). Crompton's teenage daughter, Jenny, was stabbed to death at home by her boyfriend on September 26, 1986. Before her death, the boyfriend "often gave Jenny roses as he apologized for his abusive outbreaks" (Givens 2008, p. 108).

See also OBJECT FANCY.

References:

Crompton, Vicki, and Ellen Z. Kessner (2003). Saving Beauty from the Beast (New York: Little, Brown).

Givens, David B. (2008). Crime Signals: How to Spot a Criminal Before You Become a Victim (New York: St. Martin’s Press).

TALISMAN

Object charm. A usually handheld artifact or natural object believed to have protective or other magical powers. Common examples include amulets, four-leaf clovers, lucky horseshoes and rabbits' feet.

Usage. A talisman may be carried, hung from a rearview mirror or attached to a living-room wall to bring good luck and protection, or to ward off evil (see EVIL EYE).

Word origin. A talisman is "An object marked with magic signs and believed to confer on its bearer supernatural powers or protection" (Soukhanov 1992, p. 1831). The English word derives from the 7,000-year-old Indo-European root kwel-, derivatives of which include "pain," "penalty" and "punish."

Messaging features. Through their communicative messaging features, talismans "speak" to us as gestures. A talisman may include words, symbols and other brief communications crafted into its design. Meaningful marks, lines, shapes, textures, colors and decorations may be added to transmit information apart from the object's own material functionality, durability or shape.

Neuro-notes. Nonverbally, a lucky horseshoe or rabbit's foot has a great deal to "say." In the former talisman, the weight of iron, sensed by Golgi tendon organs, muscle spindles and Pacinian corpuscles, gives it a psychological reality, importance and gravitas. Iron has long been believed to be a natural repellent of supernatural evil forces. A horseshoe's curvilinear, open-ended shape registers in the brain's visual system as a container in which to store or distribute its magical forces. In the rabbit's foot, sensory neurons (mechanoreceptors) in the fingers and palm respond to the pleasurable softness and protectiveness of mammalian fur.

See also OBJECT FANCY.

Copyright 1998 - 2020 (David B. Givens/Center for Nonverbal Studies)

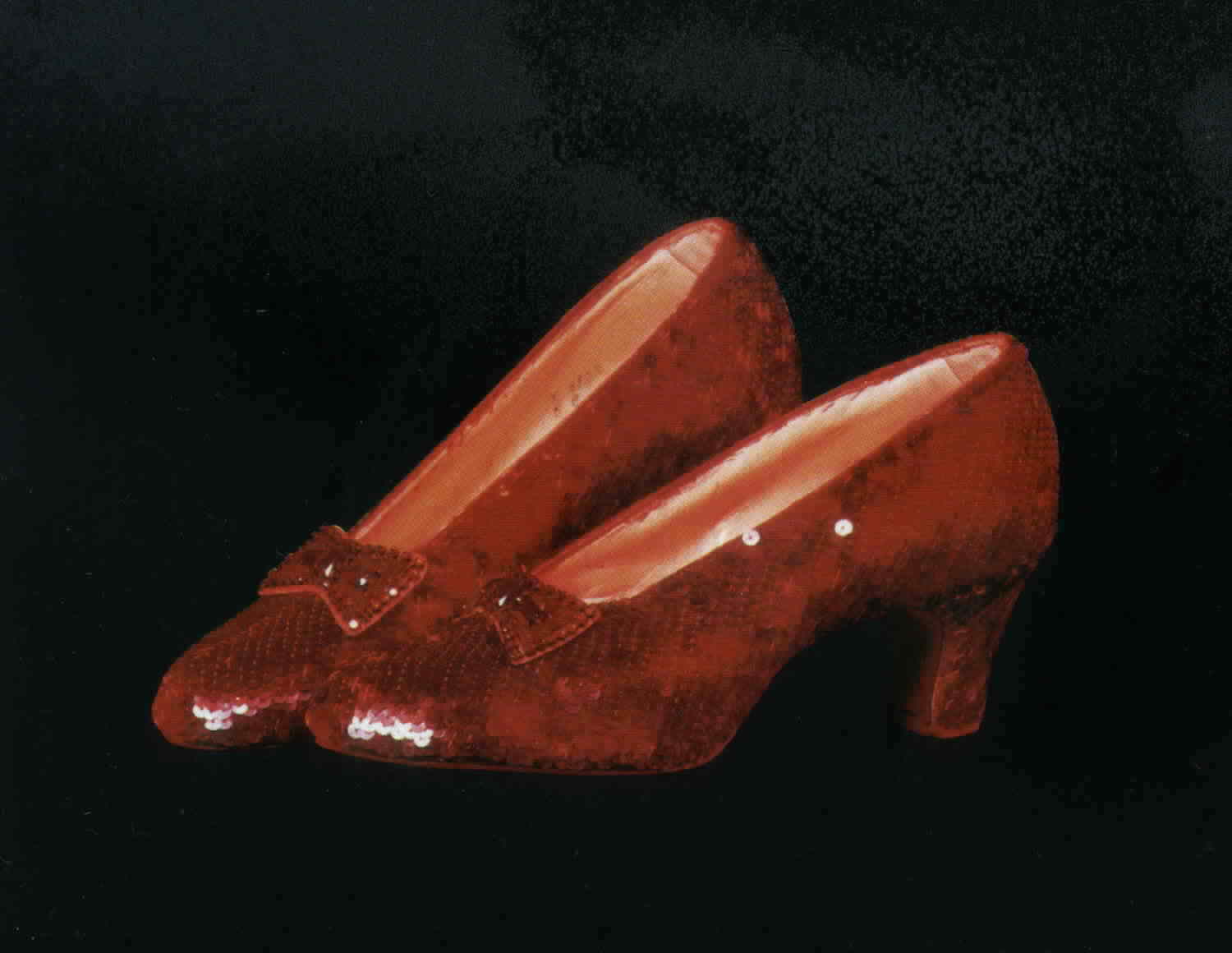

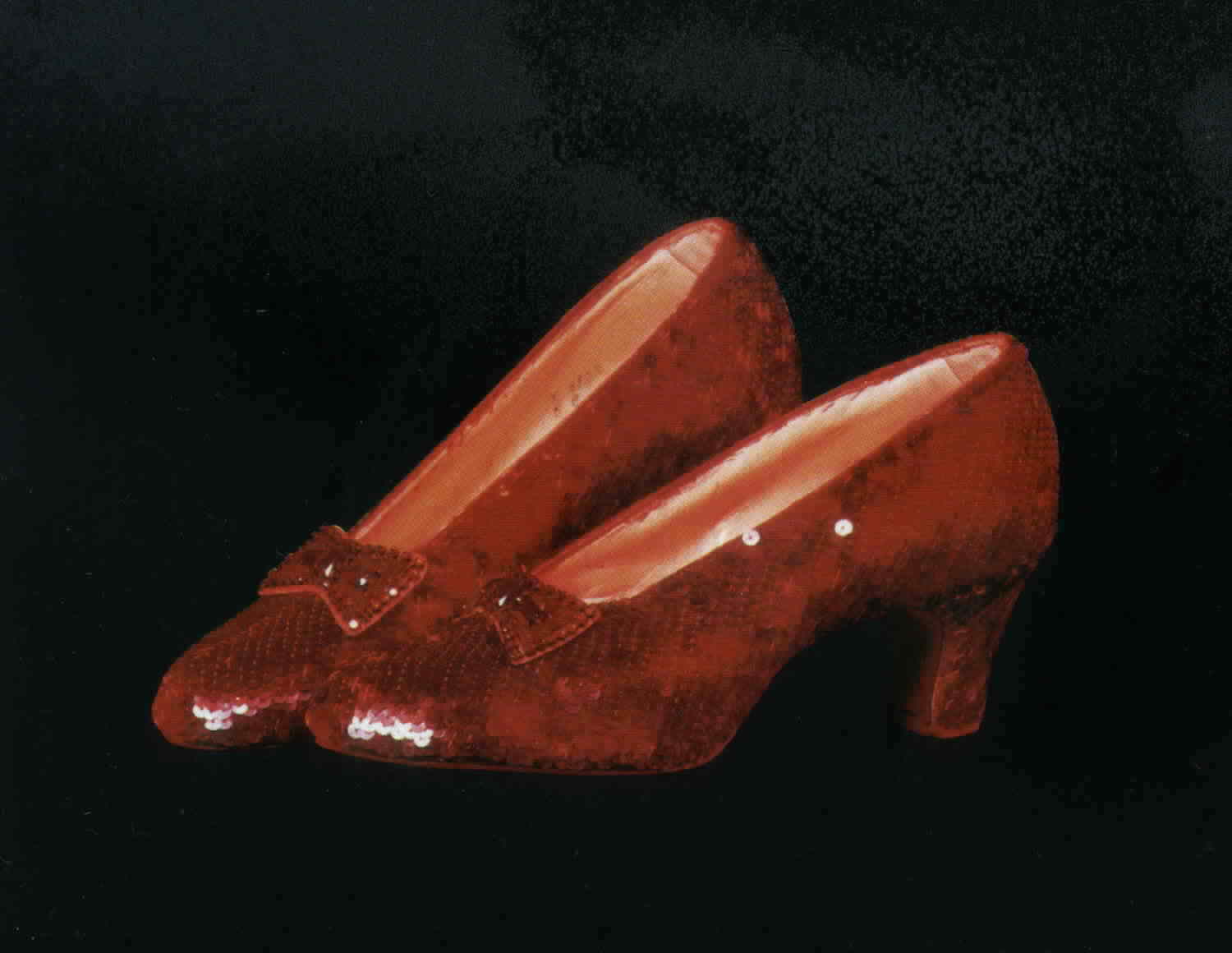

Photo of Dorothy's ruby slippers (picture credit: unknown)